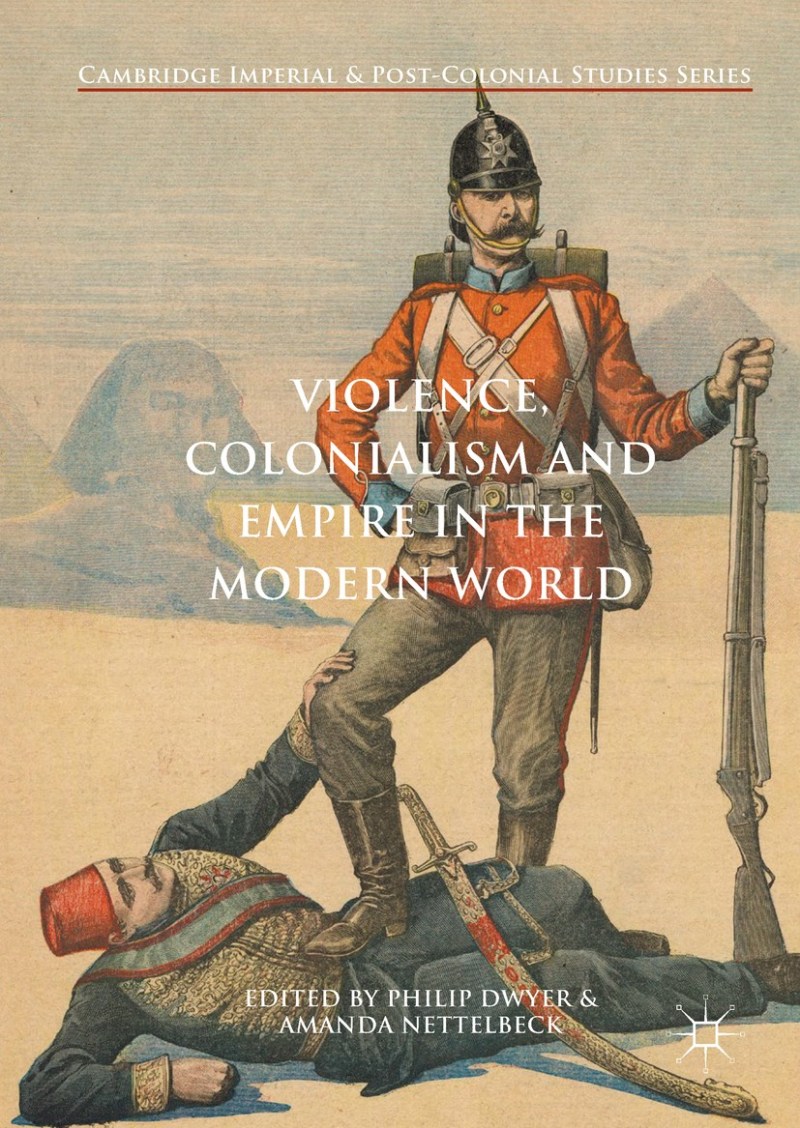

Colonialism – An 1837 watercolor depicts French troops advancing over cliffs and through a breach in the wall of the fortified city of Constantine, Algeria. Artist possibly Jean-Louis Gaspard of the 31st Infantry Regiment. Anne S.K. Brown Military Collection at Brown University Library/Library of Congress

Colonial studies on colonists developed as a separate field of research that addressed the particular circumstances of settler societies. Since its inception in the 1990s, the area has covered the Middle East and North Africa only marginally, focusing instead on the Anglophone settler societies of North America and Australasia. And yet this neglect is unjustified. Settler colonialism targeted countries throughout the Middle East and North Africa, and these efforts were key to the development of a transnational network of settler colonial ideas and practices. For the long-term development of settler colonies around the world, the Middle East and North Africa were rather peripheral to the global history of settler colonialism.

Colonialism

More than other forms of colonialism, colonialism is characterized by a “logic of elimination”. This form of rule contrasts with exploitative or extractive colonialism, where the continued subjugation of colonized populations is a requirement for the viability of colonial rule. In settler colonies, the very presence of the indigenous population is sometimes targeted through expulsion or physical elimination. Alternatively, colonial colonial powers may undermine the resilience of indigenous political sovereignty and autonomy. If settler and colonialist regimes do not show a unified investment in the direct elimination of indigenous peoples, it is because settler colonialism and other types of colonialism are commonly intertwined. The conflicting demands of subsumption and elimination can co-exist even if they correspond to different and to some extent conflicting colonial logics; all colonial regimes are marked by contradictions. Settlers also respond flexibly to conditions on the ground and to indigenous resistance and agency. However, the goal of neo-settler-colonial government is the continued dominance of the colonized collective, while the goal of settler-colonial government is the reproduction of the settler community instead of the indigenous one.

Conservation’s Biggest Challenge? The Legacy Of Colonialism (op Ed)

Indigenous scholars and activists have addressed settler colonialism for decades before the field first emerged in the 1990s; no one knew this rule better than they. Rather than opening a conversation about settler-colonial formations, scholars have provided a more global analysis. In reality, however, the field’s initial field was limited. With the exception of Israel and Palestine, settler-colonial studies have focused primarily on Anglophone settler societies—Australia, Canada, New Zealand, the United States, and to some extent South Africa. Researchers have compared these Anglophone settler societies productively in terms of their past and present: they have looked at shared legal traditions and histories of indigenous dispossession, elimination and forced assimilation. They also shed light on the parallel processes of an indigenous “renaissance” that began in the 1970s, a period that saw the rise of indigenous militancy, political organization, and increased demands for land and language rights, self-determination, sovereignty, and constitutional recognition.

From its inception, settler-colonial studies also focused heavily on Israel-Palestine. Here, too, there was a pre-existing tradition of comparative analysis of settler colonialism as a distinct mode of domination. Building on an earlier popular Palestinian critique of Zionism that dates back to the early twentieth century, Palestinian intellectuals began to explicitly denounce Zionism as a colonial colonial movement from the mid-1960s.[1] Around the same time, a small group of anti-Zionist Jewish leftists in Israel, along with Palestinian citizens, began repeating the same accusation. (The fact that their critique appeared towards the end of the war in Algeria – another settler colony – is no accident.) The development of the settler-colonial paradigm as a viable lens to interpret the ongoing conflict in Israel and Palestine began in the 1980s. . but expanded significantly at the turn of the twenty-first century. This lens has become particularly compelling as a way to understand in a single framework many issues that scholars and activists have long dealt with in isolation: the long history of Zionism as a political movement and the range of political arrangements that Palestinians experience, both as citizens. Israel. , residents of East Jerusalem, occupied subjects in the West Bank and Gaza, or refugees in the diaspora. The settler-colony paradigm has allowed scholars to offer a unifying account of the Zionist movement’s (and later Israel’s) deployment of various forms of subjugation and political fragmentation across time and space.

Since emphasizing the importance of “Third World” solidarity, many Palestinians have come to focus on “Fourth World” indigenous internationalism—a politics of transnational indigenous opposition to settler colonialism as a specific mode of domination.

The growing application of the settler-colony paradigm to Israel and Palestine evolved alongside a shift in how many Palestinians understood their liberation struggle within the wider arena of anti-colonial politics. Since emphasizing the importance of “Third World” solidarity, many Palestinians have come to focus on “Fourth World” indigenous internationalism—a politics of transnational indigenous opposition to settler colonialism as a specific mode of domination. This political change framed the United States with its own legacy as a settler colony—not as an imperialist power located abroad and acting locally through an intermediary, but as a political community directly involved in Israel’s settlement project.

Conservation And Colonialism

Israel and its policy proponents have watched the paradigm spread in academia and public culture, and in recent years have responded to it with an updated counterframe. In the 1950s and 1960s, Israeli officials usually rejected accusations of settler colonialism on the grounds that Zionism in its reconstructions was an anti-colonial movement and that the violence that accompanied the birth of the state in 1948 was in fact an anti-colonial war. liberation against the British Empire. However, if the charged debate over Israel’s colonial status has become relatively more muted in the following decades, its recent increasing prevalence has given rise to the circulation of sharper claims about the country’s Jewish origins. (These claims remain unpersuasive; one cannot claim a right to the Promised Land from elsewhere, as the Bible text and Zionist claims do, while arguing that they have always been there. Jews can “return” to the land, but they are These counterclaims often appear alongside arguments about the racial diversity of Jews and their status as “people of color”—a response to growing ties between the Movement for Black Lives Matter and Palestinian solidarity activists, as well as accusations that Zionism and the State of Israel are rooted in the principles and practices of white supremacy.

Apart from Israel and Palestine, settler colonies in the Middle East and North Africa have tended to be overlooked by scholars in settler colonial studies. This relative neglect has left unexplored the region’s crucial contributions to the global spread and development of settler colonialism as a historical phenomenon. Scholars have largely ignored that, at least between the 1830s and 1830s, European settlement in North Africa was seen as a more favorable prospect than establishing colonies further afield. (In the early twentieth century, Zionist leaders who fatefully chose to focus on Palestine rather than take advantage of potential opportunities in Argentina and Angola, among others, reached the same conclusions.) Unlike European settlers elsewhere, those in North Africa were ultimately . expelled and therefore did not survive as communities. This is not to say that settler colonialism as a distinct mode of domination was never significant there. Indeed, the modern comparative distinction between different categories of dominion, which later supported the emergence of the field, was first offered with regard to French Algeria between 1830 and 1962. Local analyzes again foreshadowed the paradigm. in his book

The Algerian intellectual Malek Bennabi, who appeared in 1954, offered an early definition of settler colonialism as distinct from other forms of colonialism. Bennabi explicitly distinguished conquered or occupied countries from “colonized” countries (a distinction that reproduced the “colonie d’exploitation”/”colonie de peuplement” opposition that characterized the French colonial tradition).[2] These would now be understood as settler colonies.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/GettyImages-1055146908-8cd571be94e340369e1f3394709e40b6.jpg?strip=all)

The form of French colonization of Algeria was itself a product of transnational comparisons. In 1831, member of parliament and academic Alexis de Tocqueville visited America and endorsed what he saw as a successful model of non-revolutionary republicanism. He later imagined that Algeria, conquered a year earlier, could become the cradle of a similar republican project. After visiting a French colony in 1841, Tocqueville supported the necessary role of violence—as well as the necessity of suspending political liberties—to complete the colonial project of the state. The following years of violent conquest culminated in the defeat of the anti-colonial leader Emir Abdelkader. After these events, progressive Saint-Simon principles became central to the redefinition of France’s civilizing mission and ushered in a brief period of liberal association between colonizer and colonized. This dominant approach ended in 1870, when the architects of the Third French Republic sought legal assimilation of Algerian and colonial institutions and deepened inequalities between Europeans and natives.[3] Later, the colony remained a testing ground for the implementation of policies that could be introduced in the metropolis.

How Colonialism Has Shaped The Design World

French republican traditions in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries praised the colonization of Algeria as an opportunity for national regeneration and a laboratory for

British colonialism, dutch colonialism, settler colonialism, spanish colonialism, neo colonialism, italian colonialism, colonialism pdf, colonialism postcolonialism, french colonialism, german colonialism, colonialism timeline, colonialism game