Most Valuable Signature Declaration Independence – Today’s post comes from Megan Huang, an intern at the Office of National History. Visit our 4th of July webpage to learn more about the Proclamation and celebrating it in the National Archives.

Before people came to see the Declaration of Independence in the National Archives, the Declaration came to people, only in a different form than it is shown today.

Most Valuable Signature Declaration Independence

When the Second Continental Congress declared independence on July 4 in Philadelphia, a farmer in Charleston, South Carolina, or a trader outside Boston, Massachusetts, might not hear the news for several days. With decades and centuries of television, telephones, and the Internet, people read news broadcasts regularly via the written word. Broadsheets—large sheets of paper printed for posting in public places—were a common means of spreading the word.

Declaration Of Independence Signed On July 4, 1776

The breadth is the way most people read about the Congressional Declaration of Independence. Specifically, from Dunlap Broadside.

Dunlap Broadsides is so named because it was printed by John Dunlap, a Philadelphia printer who would eventually become the official printer for Congress in 1778. On the night of July 4/5, 1776, Dunlap printed the most important document of his career with this first edition of the Declaration of Independence. In doing so, he produced the first published and published version of the Declaration.

The exact number of copies Dunlap printed is unknown, but has been estimated at around 200—enough to comply with Congressional orders for copies to be distributed among states and new armies, read aloud, and posted in public places.

Congress kept a copy, which was included in the Rough Journal of the Continental Congress for July 4 entry, and George Washington had his own personal copy. His troops heard the Proclamation read on July 9 in New York City. That night chapters of Sons of Liberty got together to tear down and destroy a bronze statue of King George III on the south side of Broadway, during the Revolution.

The Fight Behind The Declaration Of Independence

The National Archives is famous for displaying thick copies of the Proclamation parchment, but less well-known is that it also owns Dunlap Broadside. It was shown only occasionally as a special documentary exhibition—only 26 known copies remain.

While today the Declaration is considered one of the most important documents in American history, its 18th century creators may have cared less about its legacy and more about its current goal of explaining why they were colonized and controlled by the British Empire. on July 3rd and the 13th United States citizen on July 4th (ignoring the minor detail that this freedom still exists, it should actually work).

This goal was evident at Dunlap Broadside. Its content is the same as the highlighted version shown in the National Archives, but the use of simple type instead of calligraphy and the lack of an illuminated signature (which Dunlap was unable to print even if he wanted to, since delegates signed the August 2 Declaration) make us notice the words the original said.

Clearly distinguishing the crimes of King George III is another important distinction that reflects the Declaration’s intention to support a vote for independence.

July 4th: How Many People Signed The Declaration Of Independence?

The Proclamation had appeal as the “official” version, but in 1776, Dunlap’s version was actually the one most people would be familiar with, given its wide circulation. Branches help ensure this as most publishers are based in their own publishing houses outside of Dunlap. In contrast today, more people during the revolution saw Dunlap’s version, or iteration, than the abridged version shown here in the National Archives.

This Independence Day, visit the Declaration of Independence on display at the National Museum, and watch our video on Dunlap Broadside to learn more about its history:

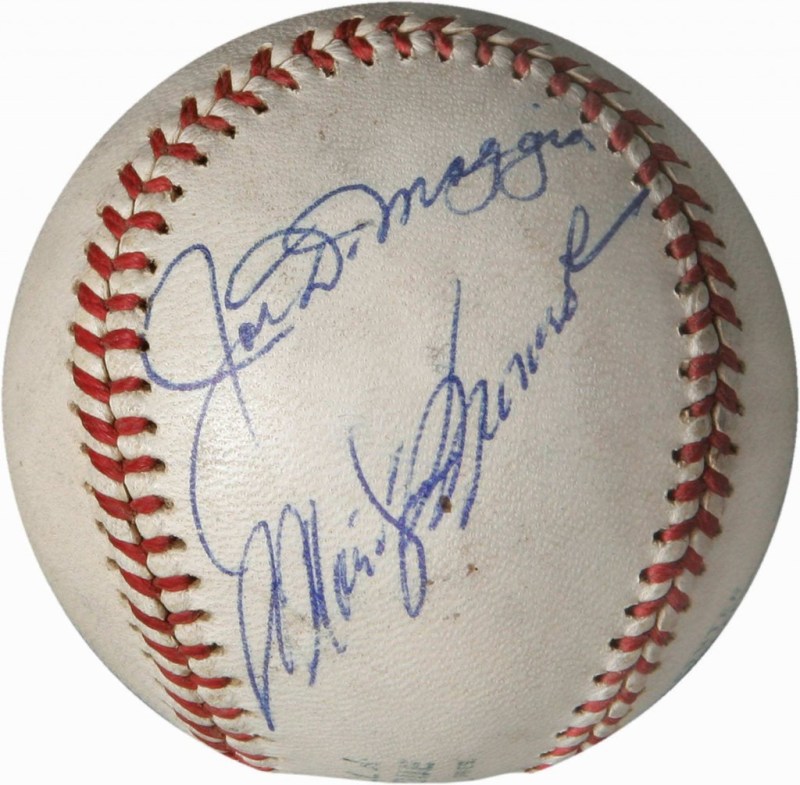

Abraham uncoln american history bill of rights essay on civil war contest congress. Congress225 Constitutional Day Constitutional Convention to Expose Civil War Eisenhower Presents FDR Franklin D. Roosevelt George Washington Post-Immigration Guest JFK John F. Kennedy LBJ lincoln NARA National Archives National Archives and Administrative Records Nixon National Archives Building Incredible History Caption Contest Photo Piece History library presidency president magazine blog random history of slavery us history of uncommon veterans US history White House history of women World War II World War II World War II We think this fact is self-evident: John Hancock’s signature on the Declaration of Independence was enormous. But what if the problem wasn’t that Hancock’s signature was too big—but that someone else’s was too small? What if it’s just Hancock

Hancock’s signature is undoubtedly the largest, and by a wide margin. According to my measurements, Hancock’s signature is 1.3 inches tall and 4.7 inches wide. This leaves the box to cover a signature 6.1 inches square. Compare that to Sam Adams’ signature, which requires only 0.6 square inches of surface area. Here is a list of all signatures, from largest to smallest:

The Revolutionary War And The Jews

The values above are all based on the digital equivalent of a “hard” copy of the Declaration. The attached copy is not the first published Declaration of Independence. The first published version was known as Dunlap’s flyer and was signed only by John Hancock, then president of the Continental Congress, and Charles Thomson, his secretary. It was written in letters and printed on July 4, 1776, and distributed to the colonies. After Dunlap’s pamphlet was published, the Proclamation was handwritten on a sheet of parchment and certified as true by members of Congress. This handwritten version is deep copy. That — or his engraving made in the early 19th century

Century, when the former begins to fade – something you usually see in textbooks or patriotic montages. Unlike the Dunlap flyer, the embossed copy has the names of 56 signers, including Benjamin Franklin, Thomas Jefferson, and John Adams. Now on display in the National Archives.

As you can see, the printed copy has a lot of blank space, including the 6.5-inch-wide and 5-inch-high box in the lower-left corner:

In trying to determine whether John Hancock’s signature was too large, there are two important questions to answer. How did these people sign the document? And according to Hancock, how many men can she sign?

True Copy Of The Declaration Of Independence

The first is simple. The consensus view among historians is that John Hancock, in his capacity as president of Congress, would have been the first to sign. For the purposes of our thought experiment, I’m going to assume that Hancock was the first signatory and set the tone for those who followed.

The second question is more difficult. It turns out that many basic facts about signatures are disputed by historians. Did Hancock know that 56 men would eventually sign the document when he put pen to paper? Or will he sign less, and thus have more room to sign?

We know a lot: You can’t match Hancock’s 56 signatures on leather. If all 56 men signed the declaration in its entirety, the document would need about 5.5 inches of vertical space to accommodate all the names—even with tight spaces and small margins:

If Hancock had asked all 56 signatories to sign sizes and everyone was present, his signature and theirs would be closer to 3.1 inches square. It is roughly half the size of the original Hancock, though larger than most of the signatures on the document. It seems to match William Ellery’s signature, the second largest on the Declaration.

John Hancock’s Declaration Of Independence Signature: Was It Too Big?

But what if Hancock expected fewer players? As it turned out, it was impossible for him to know the exact number of people who would be signing. Document signing process, and it’s very confusing. Several of the men who were members of the Second Continental Congress in July 1776 did not sign it—and several of the men who signed it were not members of the Second Continental Congress in July 1776. For example, the signer Matthew Thornton of New Hampshire was not a member of Congress until months after July 1776. Some of the members Congress at the time the Declaration was drafted, like John Dickinson, was not signed. Thomas McKean was a member of the Continental Congress representing Delaware in July 1776 – but some historians believe he didn’t sign the document until.

Although we celebrate the 4th of July as our nation’s birthday, most historians believe that most of the signers wrote their names on the sealed copies later in the summer, on the 2nd of August. Could everyone who signed on August 2 enter the Proclamation at Hancock’s size? Maybe we could forgive Hancock his big signing if he left room for big autographs for everyone in the room with him that August day, right? It’s not his fault he got involved

John hancock signature on the declaration of independence, most valuable signature on declaration of independence, declaration of independence signature, first signature on declaration of independence, 1st signature on declaration of independence, sam adams signature declaration of independence, most of the text of the declaration of independence, benjamin franklin signature on the declaration of independence, john adams signature on the declaration of independence, thomas jefferson signature on declaration of independence, most valuable signature, big signature declaration independence